Griffith J. Griffith sentenced to 2 years in San Quentin Prison for shooting and maiming his wife!

Griffith Jenkins Griffith is fondly remembered today as the namesake of a massive urban park and an enchanting observatory lying therein. But the redundantly named philanthropist was infamous, in his day, for something else: he was the O.J. Simpson of his day – the first celebrity in Los Angeles to try to murder his wife.

Griffith Jenkins Griffith is fondly remembered today as the namesake of a massive urban park and an enchanting observatory lying therein. But the redundantly named philanthropist was infamous, in his day, for something else: he was the O.J. Simpson of his day – the first celebrity in Los Angeles to try to murder his wife.

Born in South Wales in 1850, Griffith immigrated to America, penniless, at the age of 15. He eventually settled in San Francisco and got a job as a reporter, covering mining for the Alta California.

Mining was big business in 1870s California, and Griffith decided that, rather than writing about it, he’d prefer to get in on the action. And so he used inside information he learned on the beat to invest in various companies about to strike it rich. It took him less than four years to amass a great fortune. By the time he moved to Los Angeles in 1882, at the age of 32, he was a millionaire.

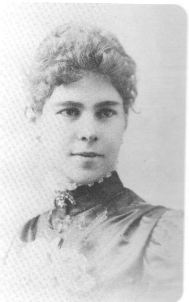

Once in LA, Griffith added to his fortune by investing in real estate, buying more than 4,000 acres of what was then known as Rancho de los Feliz, essentially modern day Los Feliz and Griffith Park, bounded to the east by the Los Angeles River. His bounty grew even bigger when he married rich – to a 23-year-old-woman named Mary Agnes Christina Mesmer (or Tina), descendent of one of the early land barons in California.

In 1896, the Griffiths presented what they called a “Christmas present” to the “plain people” of the city: a staggering 3,015 acres of Rancho Los Feliz. The gift came with one condition. As Griffith told City Council:

It must be made a place of rest and relaxation for the masses, a resort for the rank and file, for the plain people. I consider it my obligation to make Los Angeles a happy, cleaner, and finer city. I wish to pay my debt of duty in this way to the community in which I have prospered.

The park would later swell to 4,310 acres, making it one of the largest urban parks in America (dwarfing Central Park’s piddling 840 acres).

Not surprisingly, Griffith was widely reviled by the “plain people” in Los Angeles, and possibly the un-plain ones too – and this was even before he shot his wife. According to Uncle John’s California Edition of the Bathroom Reader:

Newspapers praised Griffith’s “princely gift,” but those who knew him had other things to say. Several former acquaintances and associates called him “pompous” or “a midget egomaniac” (because he was short). They also said he was a liar. For one thing, even though he called himself a colonel, Griffith had only served in the reserves, not the active military. And the closest he ever came to an official title was “Major of Riflery Practice,” an honor bestowed on him by some of his friends in the California National Guard. The phony colonel made boring speeches at his exclusive men’s club… but the club couldn’t throw him out because he gave so much money.

He was also a drunk. Although a self-professed teetotaler who even went so far as to five money to the temperance movement, Griffith was a bad alcoholic who, when in his cups, could become paranoid and delusional.

On September 3, 1903, the couple was vacationing in Santa Monica, staying at the presidential suite in the Arcadia Hotel. Griffith, drunk, somehow became convinced that his wife, a Catholic, was in league with the Pope to poison him (a Protestant) and steal his money. He pulled out a gun and told her to get down on her knees. Just as he began to pull the trigger, she jerked her head. The bullet passed through her left eye. Amazingly, she got up and threw herself out hotel window, landing on an awning two stories below. Her arm was broken and she would lose the eye, but she survived, and her husband was arrested.

To defend him Griffith hired the Johnnie Cochran of his day – Earl Rogers, who would, over the course of his career, defend 77 accused murders. He lost only three times, and would become the inspiration for the title character in the book series Perry Mason, later adapted for bot radio and TV. (He would also defend Clarence Darrow after Darrow was accused of jury tampering in the trial of the McNamara brothers, who were accused of bombing the LA Times building. Darrow and Rogers fought constantly over Darrow’s behavior during the trial, which resulted in an acquittal.)

For Griffith’s trial, Rogers employed an untested tactic, an early precursor to the Twinkie defense: the booze defense. Rogers argued that Griffith was not guilty by reason of “alcoholic insanity.” Witnesses testified to Griffith’s alcoholism and paranoid behavior. Even Tina, her disfigured face hidden behind a veil, confirmed, under cross examination, that her husband was an alcoholic prone to wild, delusional outbursts. The jury had no choice but to acquit Griffith of attempted murder, although they convicted him of a lesser charge, assault with a deadly weapon. The judge gave him two years in San Quentin and ordered that he be given ”medical aid for his condition of alcoholic insanity.”

After the trial, Tina sued for divorce. A judge granted it to her in less than five minutes – the fastest divorce in the history of Los Angeles. Somewhere along the way, Griffith was humbled, and in prison, he got sober. He declined to apply for parole, opting instead to serve the entire two years. His conduct was called exemplary.

While in prison, Los Angeles had renamed Mount Griffith Mount Hollywood. When he got out, Griffith was ready to restore his reputation. According to Uncle John:

In 1906 he returned to L.A. – now sober, still rich, and fully determined to improve his image with the “plain people” who enjoyed Griffith Park. Unfortunately, the plain people despised him.

In 1912, Griffith offered another “Christmas present” to the city of Los Angeles: an amphitheater and a science building, to be built at his expense inside Griffith Park. City Council was inclined to accept the gift, but in the face of public protests, the Parks Commission blocked the vote.

But Griffith had the last laugh. Sort of. When he died on July 6, 1919 of liver disease, the lions share of his $1.5 million estate was left to the city of Los Angeles, much of it earmarked for the expressed purpose of building what would become, in 1929, the Greek Theater, and in 1935, the Griffith Observatory. Today, the park and observatory that share his name are world famous; the attempted murder of his wife is long forgotten.

The moral of the story: in Los Angeles, if you’re rich enough and patient enough, you can get away with anything.