The following is a script from “Mountain Lions of L.A.” which aired on Jan. 17, 2016. Bill Whitaker is the correspondent. David Browning, producer.

What do you do when you cross paths with a mountain lion? It’s in their nature to avoid people. Attacks happen but they’re extremely rare. Experts say if you stand tall, wave your arms, yell, but don’t run, they’ll back off. In Southern California, that’s advice worth remembering.

Los Angeles and its suburbs are home to 19 million people — the only megacity in the world where mountain lions, also known as cougars and pumas, live side-by-side with humans. For 13 years, the National Park Service has been studying the animals: opening a window on their mysterious world and raising questions about their survival in the land of freeways and suburban sprawl. They’re the unseen neighbors up the hill. And sometimes, they come to call.

14 Photos

Big cats in a big city

Bill Whitaker: When you moved here, did you know that there was a mountain lion in the vicinity?

Paula Archinaco: No. No. Not at all. Not at all. There’s signs for rattlesnakes. There’s not signs for mountain lions.

[Bill Whitaker: Some view you have here…]

Paula and Jason Archinaco’s house is something of a local landmark: not just for the killer view of Los Angeles, but also for an encounter a workman had one day in the crawl space under the house. He was doing some wiring when he saw something scary.

Jason Archinaco: He comes into my office terrified. And he says, “Bro, you have a mountain lion in your house, bro.” And so I said to him, “A mountain lion?” And he goes, “Yeah, man, a mountain lion, face-to-face, eye-to-eye, it came eye-to-eye with me.” And he was like terrified.

He had been eye-to-eye with P22, so named by the Park Service: “p” for puma, number 22 out of 44 they’ve studied, photographed here with a small camera on a very long stick. P22 wears a park service tracking collar that sends GPS signals on his location. Signals that were blocked this day because he was under the house.

Paula Archinaco: He was just laying there, trying to snooze, completely just like, we woke him from a nap.

Soon the house was packed with cameras and reporters. P22 was already a local celebrity because of this National Geographic picture, taken by a remote camera a mile or two from the Archinacos’ house. Wildlife experts finally decided to shoo everybody out after the 11 o’clock news, hoping P22 might head back into the hills nearby which he did.

Bill Whitaker: So when did he leave? How did he leave?

Paula Archinaco: We don’t know how.

Bill Whitaker: They call ’em ghost cats.

Paula Archinaco: There you go.

And though they live in the shadows, in much of Southern California they’re never far away. A trail camera caught this one a stone’s throw from the rooftops of suburbia.

Jeff Sikich: These animals do their best to, you know, stay elusive and away from us. Even us researchers, who follow them almost daily, we hardly ever see them.

Jeff Sikich is a Park Service biologist, an expert on big cats who holds something of a record: he’s seen and captured P22 four times now.

This time, he corners the animal and hits him with a tranquilizer dart. Quickly, it knocks P22 out, with his eyes still open. The batteries on his GPS collar were running low. Replacing them gives Sikich and his crew a chance for a checkup. P22 is healthy, weighing in at 125 pounds. From experience, Sikich knows that when the animal comes to, it’s no threat: the instinct to get away from people kicks in. Sure enough, a groggy P22 wakes up and stumbles back into the shadows.

Jeff Sikich: Here’s the past eight months of where P22 has traveled.

The GPS signals from their collars tell Sikich and his colleague Seth Riley where the animals roam. P22 wanders the hills of Griffith Park, a small enclave in Los Angeles frequented by hikers and visitors to the park’s famed observatory.

Seth Riley: We haven’t, knock on wood, had any major conflicts with him and people. And it shows that even a large carnivore like a mountain lion can live right among people for many years.

They think P22 migrated east across the Santa Monica Mountains for 20 miles or so, perhaps chased out by a bigger male. He somehow crossed the 405 freeway, one of the world’s busiest, worked his way through Bel Air and Beverly Hills. And, somewhere near the Hollywood Bowl Amphitheater, crossed a second busy freeway, the 101, to Griffith Park.

Jeff Sikich: P22 had it great. No competition. No other adult males in Griffith Park. Seemed to be plenty of prey for him.

He’s been in Griffith Park for three years now: all alone, looking for love in all the wrong places.

Jeff Sikich: Yeah, you know, still hanging out there, which is pretty surprising. I would have bet he would have left looking for a potential mate.

If the mating urge overwhelms him, he could take his chances crossing the freeways again to find a female. A very risky business.

Bill Whitaker: Why not move him?

Jeff Sikich: Usually it doesn’t work moving lions. We’ll just be moving this animal, this adult male, into another adult male’s territory. And that usually results in the death of one of ’em.

And in the Verdugo Mountains, a small range overlooking the San Fernando Valley, there’s another lonely lion.

Nancy Vandermey: I never thought one would actually come through our backyard. And he was right next to our bedroom window.

Nancy Vandermey and Eric Barkalow moved here to be close to wildlife. And got their wish, in the form of a mountain lion named P41, who seems to love their backyard deck.

p-41-steps-nancy-vandermey-and-eric-barkalow.jpg

P41 is caught on a home surveillance camera

Nancy Vandermey and Eric Barkalow

Bill Whitaker: So he’s right out here where we are.

Nancy Vandermey: Exactly where we are.

He has come to visit at least 10 times, triggering security cameras taking both video and still pictures. The area is called Cougar Canyon. What else?

Eric Barkalow: Here he’s just literally made a loop around our house for some reason.

Like proud parents with baby pictures, they show off their video scrapbook.

Eric Barkalow: And let me point out how his paws are on the wood and not on the gravel so that he can make as little noise as possible. They want to be silent at all times.

Camera technology has revolutionized the way mountain lions and other wild animals are studied. Johanna Turner is a sound effects editor for Universal Studios. On her own time, she’s one of several “citizen scientists,” as they’re called, who put remote cameras up in the wild, hoping to get that perfect shot.

Bill Whitaker: How do you know where to look?

Johanna Turner: We’ll look for tracks and we’ll look for signs of them. And we look for deer, because that’s their food source.

To lure the lions into camera range, she’ll sprinkle catnip, vanilla extract, even men’s cologne on a branch. And just like housecats, they love it.

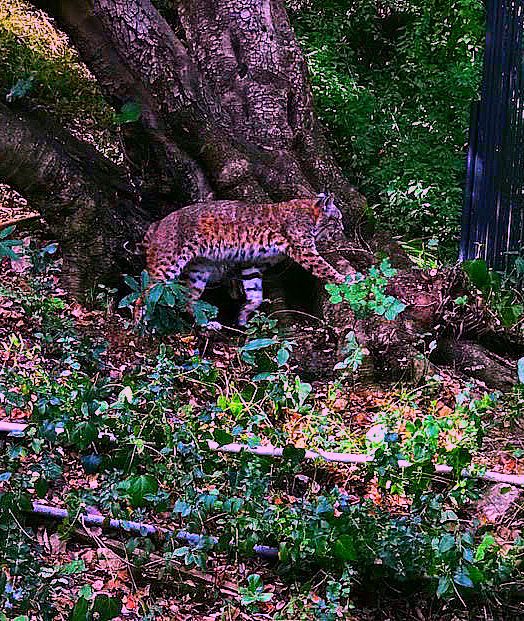

The Holy Grail is a shot like this one, of P41. But her cameras also catch bobcats, coyotes, foxes and bears: trouble-makers.

Johanna Turner: You come and find that a bear has, you know, turned the camera sideways or licked the lens or something. And that happens weekly.

Bill Whitaker: What’s the most amazing thing you’ve seen?

Johanna Turner: My favorite is a video of a female mountain lion and her two kittens, and they’re nursing on her. I still can’t believe that happened. That she decided to lay down right in the front of the camera.

Science is learning much more about what happens when the lions are penned in by freeways and houses. The Santa Monica Mountain range is about 200 square miles, the area usually staked out by just one male mountain lion. Here, there’s often a mix of a dozen or so males and females.

Bob Wayne: It’s a family you wouldn’t want to belong to….

Bob Wayne is an evolutionary biologist at UCLA. Using DNA from the blood samples taken by the Park Service, primarily in the Santa Monica Mountains, his scientists have built a family tree, unlocking some strange and deadly secrets.

Bob Wayne: It’s just rife with incestuous matings. It’s not a healthy situation.

The DNA shows males are mating with their own offspring. And killing them as well. Sometimes even killing their mates.

Bill Whitaker: And that doesn’t happen in the wild normally?

Bob Wayne: Rarely. Both the incest and this excessive amount of strife are very unusual.

Bill Whitaker: You think that is all because of this limited amount of space they have?

Bob Wayne: It is.

And on some primal level, they long for more space. At least 13 have been killed in traffic in recent years, trying to move on. It’s a double-edged sword: being penned in, the lions can’t get out to the wide open spaces away from the city – and the incestuous inbreeding will only get worse if lions from the wilderness can’t get in, to mate and strengthen the gene pool. But there is a possible solution.

It’s an ambitious plan to build the animals an overpass on the 101 freeway to open up a migration route. It’s been done elsewhere in the world – this one crosses the Trans-Canada Highway in Banff National Park. At the proposed site on the 101, the freeway is 10 lanes wide, traveled by 175,000 cars a day. It would be a complicated, costly project.

Seth Riley: It would be an amazing statement to say, “OK, we care this much in Southern California about wild places and wild animals that we would do this and make a place for animals to get back and forth.

Bill Whitaker: Is that their only hope?

Jeff Sikich: Pretty much for our Santa Monica mountain lion population, yes.

And what about future generations?

Jeff Sikich: That’s a pretty good signal.

The beeps are coming from a collared female lion, P35. Researchers think she might have a newborn kitten or two at one GPS location where she’s been spending a lot of time. When the signals show P35 is a safe distance away from the spot, Jeff Sikich moves in: working on sheer intuition, looking for a needle in a haystack.

And he finds it. A feisty, three-and-a-half week old female,

P44

National Park Service

Her blue eyes will change to amber in a few months, the spots that camouflage her will disappear.

Sikich and his crew work in whispers, in case the mother is within earshot. P44 is given tags to identify her on trail camera pictures. She appears healthy: but given the danger she faces on the edge of civilization, her future is a question mark.

Jeff Sikich: Alright, time to go back.

All Jeff Sikich can do is put her back where he found her, to take her chances in the shadow of the city.

Like these a lot better than the shot I have of one of these beauties (or a relative) gazing amid beer cans, food wrappers, cigarette butts and toilet paper below the “Vista” site.

Let me know if you would like any images from my “weird bugs of Beachwood” collection 😉